The simple density formula of mass over volume doesn’t exactly translate to literature in a useful way. The average paperback novel, for example, has a density of about 7.2 grams per centilitre, but this tells us little about the literary content of the text. And if we consider ideas like the hypertext fiction of Storyspace, like Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger for example, calculating density in the traditional fashion becomes senseless. Therefore, a more novel version of the formula is needed.

Substituting mass for word count: the material of a novel, and volume for page count: the container of the material, the formula for calculating density of a piece of literature becomes word count over page count.

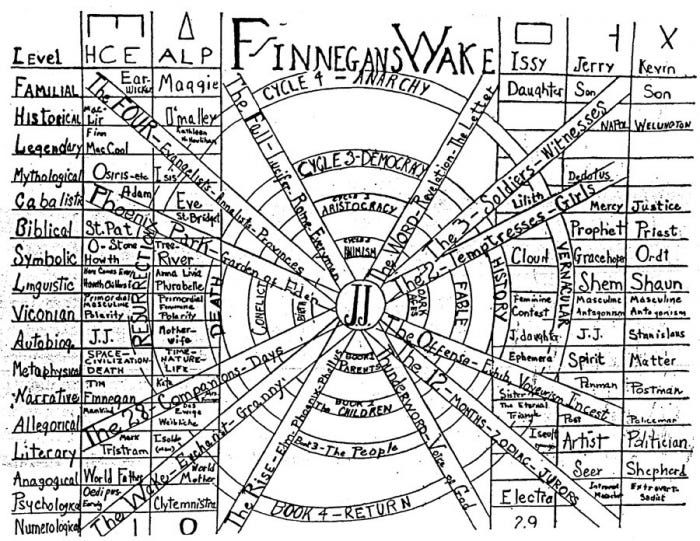

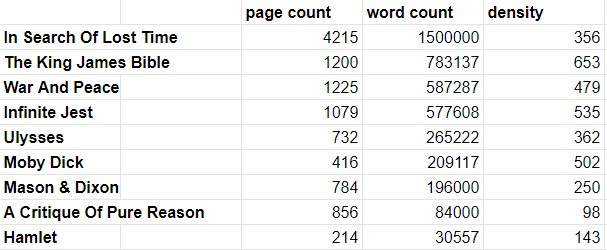

With this in mind, let’s survey the literary densities of a few various titles that are often considered traditionally dense (mass over volume):

Surprisingly, Marcel Proust’s In Search Of Lost Time, the leader by a long shot in both word count and page count, ranks sixth in density, with a density of only 356 words per page. This is quite average, measuring a little about the average density of all novels, which hovers somewhere around 300 words per page.

The King James Bible is the densest text on the list with 654 words/page. With all it’s family lineages and instructional passages and frequent use of asyndeton, this seems intuitive.

The encyclopedic style of David Foster Wallace’s meta-modernist tomb, Infinite Jest, ranks high on the list at number 2 with a density of 535 words/page, just a little above the Magnum opus of the American renaissance, Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, with a density of 502 words/page.

While not technically novels, the data gathered from the stage plays of Shakespeare and the philosophical texts of Immanuel Kant is quite illuminating.

With a density of just 98 words/page, A Critique Of Pure Reason ranks last on the survey, demonstrating the relative density of philosophical writing compared to prose of the same length.

This seems intuitive, as philosophical writing is often full of lists and charts, logic statements and diagrams, a heavy use of white space when compared to novels. While many find the philosophical style quite impenetrable, they are often less denes texts compared to the easier-to-handle style of the novel.

Hamlet is also very low on the list at 143 words/page. The plays of the bard are relatively short in length and light in weight compared to some of the weighty tombs of western literature. demonstrating the flowery poetic style of shakespeare’s writing is a far less dense literary style than the encyclopedic style of Wallace, for example.

A simple model of the densities of literary styles could be constructed, with poles of poetic and encyclopedic anchored on either side, and a gradient scale between them with various styles taking their respected places.

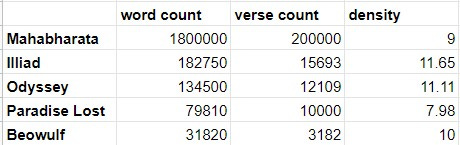

Epic poems, another large appendage of western literature, requires yet another modification to the density formula.

Page count becomes senseless with most epic poems, their “volume” value is more accurately defined by the poem’s number of verses, or verse count. The formula for the literary density of an epic poem becomes word count over verse count.

At 1800000 words, The Mahabharata is the longest entry on the list by far, but ranks second last in density at just 7.98 words/verse, 1.97 words below the average density of 9.95 words/verse.

The Iliad is the denest poem on the list, at 11.65 words/verse, just above Homer’s other epic The Odyssey, at 11.11 words/verse.

As you can see, the variance in densities of poetry is far smaller then the variance in the densities of novels, demonstrating the more constrained form structured verse offers over free prose.

The formula begins to break down a bit the more modern the poetry gets. For example, Faust was difficult to include in the survey (and was omitted because of this) due to it’s mixing of styles, changing between verse and prose several times. A formula could be imagined though, taking into account the variable densities of both prose and verse and comparing the ratios.

Trying to calculate the density of an E.E. Cummings poem for example, seems to defy the formula almost completely. Problems arise when taking an accurate word count, as ‘words’ are experimented with a great bit as a concept in modern literature.

While words per page and words per verse don’t directly convert, it seems clear that by these formulations, the poem is the less dense medium than the novel.

And yet, a sense of impenetrability looms over many of these “less dense” texts. Shakespeare is relatively light by the numbers, but takes ages to read through even just a few verses and actually comprehend what Shakespeare meant. The language and allusions are quite foreign to all but the most studied in the tales of the bard. This makes reading his words is a much slower affair then say Tolstoy’s War and Peace, despite it’s density, and demonstrates that the density metric might not be useful in calculating read time. Or perhaps it’s a sign that the formula is broken.

Things break down even more when we start to consider this missing time variable of our formula.

Certain styles take much more attention and effort to read than others. The stream of consciousness prose of the beatniks like Kerouac’s Big Sur is a gentle stroll through the mountains compared to schlog that is the analytic surreality of Hegel’s Phenomenology Of Spirit. The theory fiction of Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia or the writings of the Cybernetic Collective Research Unit defy understanding and logic at times, and can take multiple attempts to crack the surface, a far more labored affair then reading the book of exodus.

A new formula is needed including a time variable to sort out these discrepancies. Perhaps revolving around the idea of word variance: the amount of unique words in a text, or a variable that takes into account the relative length of different words within a text.

Beyond this, the time variable would have to revolve around the individual reader’s subjective reading speed and attention, and this would be almost impossible to attain on a reliable basis.

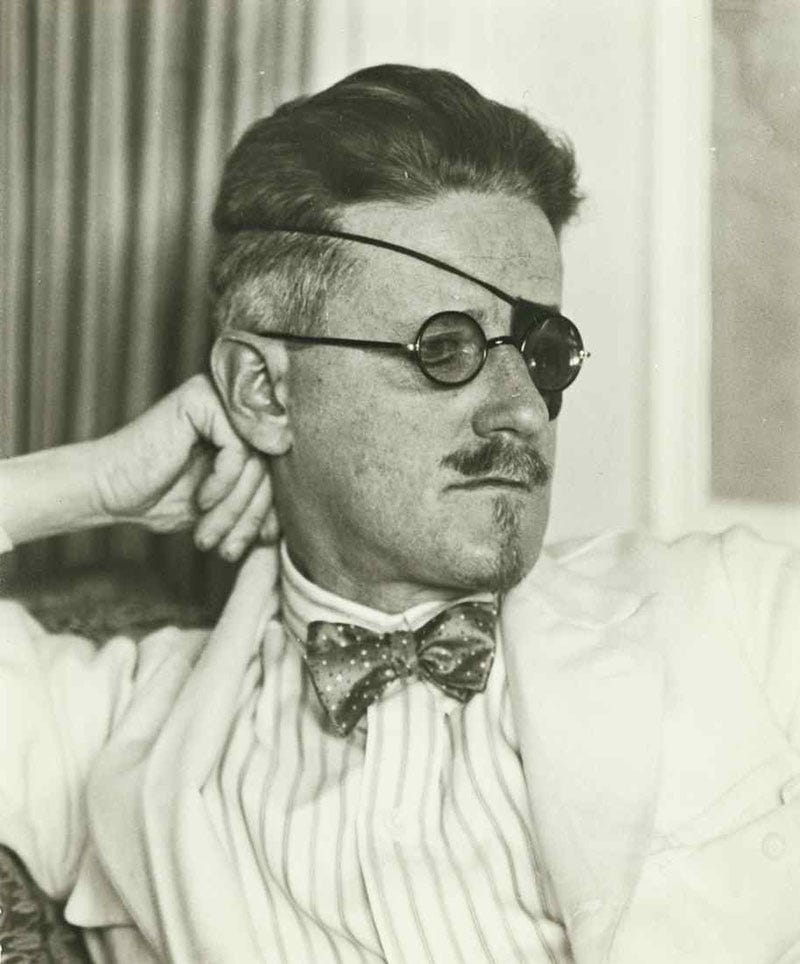

With all this in mind, let’s return to the title in the survey ranked 5th in density at 362 words/page, James Joyce’s Ulysses.

A rightful classic, Ulysses is a herculean affair to get through, one of the most challenging books I’ve ever encountered by far, and clearly demonstrates the need for a new formula for literary density. It also seemed to foreshadow Joyce’s masterpiece to come, Finnegan’s Wake, the densest novel ever written.

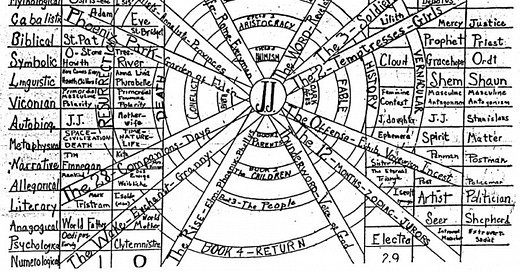

Calculating the density of Finnegan’s Wake is impossible with our current formula. The word count for the text is a highly disputed affair, as Joyce creates many new words and omits many spaces and punctuations, thus creating new words through juxtaposition. While in theory this would bring the relative word count down, the style it creates becomes this dream of a text that defies being read altogether. One picks up Finnegan’s Wake and stares at the words on the page, one does no to simply read Finnegan’s Wake. It can be read, but shouldn’t be attempted by all, and is by far the densest text in all of literature.